As a kid, I ran across the slippery stones on the banks of the Spokane River at least three times a week. I lived just upstream from the Pleasant View Bridge that was closed in May of 1971. The bridge was built in the 1920s, the center section fell out in 1953 and was patched back together to be deemed “unsafe” not even twenty years later and closed. Its closure isolated the population of Pleasant View from easy access to Post Falls, just like the demolition of the Greensferry Bridge on April 15th, 1971 had done to the residents on the southeast side of the river. Neither has been rebuilt. The effects of the Pleasant View Bridge’s closure were amplified because the Spokane Street Bridge collapsed on April 1st of 1971 throwing three men, including a policeman, into the frigid early spring runoff just upstream of the dam. 1971 was a bad year for bridges in Post Falls.

My younger brother, who now isn’t all that young, used to go down to the bridge with his friends and jump off its remnants into the river below. I’ve always thought he was either daring or foolish, but he’s managed to stay alive this long so I suppose the verdict leans more in the direction of daring. I was always too apprehensive to jump. I call it apprehensive now, but back then, failure to do it landed you in the category of being a chicken, a wuss, or a pussy. I would walk out on the bridge and peer through the holes in its concrete deck, crisscrossed with rebar, to the river below but never jump. Some of the kids, including my brother, would climb the riveted steel spans above the deck dotted with rusty patches emerging from underneath the baby blue paint and jump from up there. The last span of the deck that connected the south side was removed by the time I was old enough to venture to the remnant. I would sit with my feet dangling and look at the south bank, at the opposite end of Pleasant View Road which existed in its middle, and think about what it meant when a bridge is broken.

Although jumping off the bridge wasn’t my speed, I would walk the banks of the river cutting yellow willow branches to make a bow with orange bailing twine. I would shoot makeshift arrows at the tiny birds hanging out in the scrub brush along the banks. I never hit anything with those feeble attempts, but it kept me entertained for hours on end. I was just a twelve-year-old white kid attempting to connect with the noble savage that my cultural conditioning had told me once existed along the river’s banks—why I thought anyone would shoot at tiny birds instead of fishing in the river I blame on the folly of youth and the ignorance that accompanies it.

The river used to have salmon. I’ve never seen them, but they used to be there. They would swim from the ocean climbing fall after fall to the base of the falls my little hometown grew up around. The native men and women relied on those salmon runs. I’ve rarely caught anything out of the river, and when I have my catches were not all that impressive—I would have been one hungry guy if I had to rely on the fish in that river.

I would walk the banks of the river with my dad and we would pick up trash. There was a lot of trash along the banks back then. For a long time, people would just push their trash into the river to have it carried away downstream—out of sight out of mind. The legacy of that practice still washes up sometimes. When we would come across beer cans or whiskey bottles, no doubt left behind by teens or sportsmen who really didn’t care, my dad would make the joke that he was picking up Indian artifacts. In all the years I spent running up and down the banks of the Spokane River, a couple of miles in each direction from our house, I never once met an Indian.

When 1992 rolled around, the Centennial Trail, a bike and walking path designed to connect Spokane and Coeur d’Alene, sprouted up along my section of the river. I would ride my bike on a portion of it to get to school, a five-mile ride I preferred instead sitting idle in a bus seat—boys are not sit-down animals. In the opposite direction, headed toward Spokane, the trail stayed closer to the river. In that direction, nestled between the weigh station on I90 and the river stands a stone marker. I never paid much attention to it as a kid, I just whizzed by on my bike filled with blissful ignorance. The marker predates the trail. It was put there in 1946. The event it memorializes happened in 1858.

The first bridge that crossed the Spokane River was the Pioneer Bridge. Built in 1864, the bridge sat about halfway between my childhood home and the marker. A bridge still crosses there today, although it is slightly offset from the original—you can still make out where the original stood if you pay attention to the banks of the river. At the time, a little community sprang up on the south bank where the bridge crossed. When you drive by it now, there isn’t really anything that would indicate this was the area’s first white settlement—but I digress.

In 1858 there were no bridges that crossed the river. The government also had little interest in forming bridges with the native populations who were living in the area. If you were there in 1864 when the Pioneer Bridge was built, and you stood on it looking downstream, less than a mile away around a bend in the river, you would have seen the bleached bones 1858 left behind. People said they could see the bones piled in the clearing well into the early 1900s. If the weigh station and freeway didn’t block your view now, you could see where the marker stands from the bridge.

I must have passed the marker a hundred times as a kid never stopping to read it. It wasn’t until I went riding bikes down the trail with my kids that I took the time to stop and read it—little legs need longer rests. That was when the shell of ignorance that afforded me the ability to innocently play the noble savage along the banks of the river only a handful of miles upstream as a kid finally cracked. This is what the inscription says:

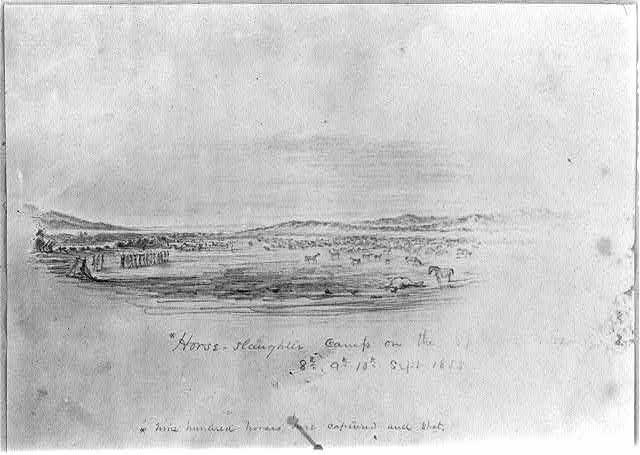

“In 1858 Col. George Wright with 700 soldiers was sent from Walla Walla to suppress an Indian outbreak. After defeating the Indians in two battles he captured 800 Indian horses. To prevent the Indians from waging further warfare he killed the horses on the bank of the river directly north of this monument.”

In school, we talked about Lewis and Clark, Manifest Destiny, and the Indian Wars, but for some reason, this never came up. We learned about the Trail of Tears where thousands of Native Americans were essentially marched to death in the south, we learned about Custer at the Battle of Wounded Knee (it was called Custer’s Last Stand in our textbooks), we learned about Colonel Steptoe’s defeat by the Spokane, Palouse, Coeur d’Alene, and Yakama tribes earlier in 1858, but the retribution Colonel George Wright exacted wasn’t covered. In the fourth grade, we had a field trip to the mission where Wright and the Coeur d’Alene’s signed the treaty—Wright’s retribution still wasn’t covered. We could literally take a long afternoon walk from our elementary school to this monument and we never covered the fact that the United States Government killed eight hundred horses (some accounts say seven hundred, some say nine) to break the Spokane tribe. We never covered Colonel Wright burning the food stores of the Spokane’s and Coeur d’Alene’s as he made his way to Father Joset’s Sacred Heart Mission in what is now Cataldo, Idaho. We learned about the cannery that canned apple butter and green beans that used to be in town, we learned about the horseracing track, we learned about Mullan’s road and Corbin’s ditch, but we didn’t learn of the systematic campaign by the United States government to suppress the area’s original residents.

As an adult, I can’t help but notice the monument refers to the incident being instigated by an “Indian outbreak.” I’ve heard of cholera outbreaks, measles outbreaks—plenty of outbreaks associated with viruses—but an outbreak of people sounds like it was straight out of Goebbels’s Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. Since the monument was erected in 1946, one year after the end of WWII, you would think we would have been more sensitive to comparing a group of people to viruses, but the evidence suggesting otherwise stands in the middle of a clearing surrounded by the drone of interstate traffic. To add insult to injury, when you look at the photograph of the unveiling from 1946, there are five white guys, three women from the Spokane tribe, and the grandson of Spokane Chief Garry, the man who signed Col. Wright’s treaty. Maybe it’s just my modern perspective, or my propensity to equate things to the bridges in the area, but it doesn’t seem that far away from how they patched the Pleasant View Bridge in the 1950s, a well-intentioned stopgap that isn’t going to age well.

The inscription on the monument has some other well-crafted narratives that reinforce the native population as bloodthirsty savages who needed to be quelled—such as, “to prevent the Indians from waging further warfare.” Learning of the incident, I sought out more information about it and came across the journal of Lieutenant Lawrence Kip, an officer who was with Col. Wright as he “[suppressed] an Indian outbreak.” His account of the incident, and subsequent events, highlight the sentiments of the time[i].

On September 9th, 1858 Lieutenant Kip notes that at daybreak three companies of dragoons were sent out to destroy seven lodges used as grain storehouses. Then he attended an officer’s meeting with Col. Wright to decide what should be done with the horses. Kip comments, “Nothing can more effectually cripple the Indians than to deprive them of their animals.” Neither the change in the wording from suppressing to crippling nor the softening effect that the distance of years can have on our cultural memory is lost on me. So, how did the United States government “deprive” the Spokane’s of their animals?

Two companies were ordered to undertake the task of eliminating the equine. They made a corral and drove all the horses into it. Then, as Lieutenant Kip writes, “One by one, they were lassoed and dragged out, and dispatched by a single shot. About two hundred and seventy were killed in this way. The colts were led out and knocked in the head. It was distressing during all the following night, to hear the cries from the brood mares whose young had thus been taken from them. On the following day, to avoid the slow process of killing them separately, the companies were ordered to fire volleys into the corral.” That was distilled to, “killed the horses on the bank of the river” on the monument’s inscription. The distillation lost its potency. On September 10th they added another two companies to wrap up the job.

As fourth-graders, we stood and recited the Pledge of Allegiance every morning. As a cub scout, I was a part of the honor guard that brought the flag in for school assemblies, where we also recited the Pledge of Allegiance. None of us knew the history of what we were aligning ourselves with. Our teachers left out huge portions that would sour the words of that pledge in our mouths. Then again, what teacher wants to console a classroom of fourth-graders after they tell them the United States Army killed eight hundred horses just a few miles from the school’s doorstep?

On September 11th Col. Wright and company crossed from the south side of the Spokane River to the north bank and began following it upstream. Presumably, they marched right across the land where my childhood home sits. Kip notes seeing the falls where Federick Post would later build his mill and the city of Post Falls. They burned another four Indian lodges filled with wheat just upstream from the falls and destroyed cashes of dried cake and wild cherries. Kip wrote, “This outbreak will bring upon the Indians a winter of great suffering, from the destruction of their stores,” reiterating that this was never about suppression, instead it was about inflicting harm, suffering, and potential eradication.

Interestingly enough, Lieutenant Kip took the time to write what he thought about the area. “When the Indian thinks of the hunting-grounds to which he is looking forward in the Spirit Land, we doubt whether he could imagine anything more in accordance with his taste than this reality.” He also noted, “This is a splendid country as a home for the Indians and we cannot wonder that they are aroused when they think the white men are intruding on them. The Coeur d’Alene Lake, one of the most beautiful I have ever seen, with water clear as crystal, is about fifteen miles in length, buried, as it were, in the Coeur d’Alene Mountains, which rise around it on every side. The woods are full of berries, while the Spokane River salmon abound below the falls and trout above.” He recognized the places were named for the people they are trying to inflict harm upon and that those people were only trying to protect their little corner of the world from being overrun by outsiders.

Kip even pontificated about the effect white men would have on the native population. “As soon as the stream of population flows up to them, they will be contaminated by the vices of the white men, and their end will be that of every other tribe which has been brought into contact with civilization.” Perhaps being “contaminated” by the vices of the white men is what led to my dad’s comment about the beer cans and whiskey bottles being uttered one hundred-forty years later—cultural conditioning runs deep.

The leaders of the Coeur d’Alene nation and Colonel Wright and his officers signed a treaty on September 17th, 1858. Not unlike other librarians, I wanted to find a copy of the original document, but it doesn’t exist. What does exist is a copy of a draft of the preliminary articles accompanied by a list of who was there and a letter written to Father Joset by Col. Wright that contains the terms which corroborate the copy[ii]. It appears that one of my fellow librarians had inquired about the original document with the National Archives and Records Service in Washington, D.C. in 1962. Francis Heppner of the Army and Air Corps Branch responded on May 7th, 1962 with the following statement, “The several letters in the records of the War Department regarding this treaty indicate that Colonel Wright sent the treaty to Colonel Newman S. Clarke, who was the commanding officer of the Department of the Pacific. That officer disapproved of part of the treaty. It appears that he forwarded a copy of the treaty to the Adjutant General in Washington and retained the signed original treaty.[iii]” As to what Clarke found so distasteful, one can look to his comments at the bottom of the copy of the treaty with the Spokane’s that he sent on. The fact remains, that this is further indication that the native peoples of the region weren’t viewed as people by the newly arrived white men—they were othered and; therefore, exploitable. Perhaps Goebbels was looking at our playbook.

Colonel Wright left Joset’s Mission the next morning with a chief of the Coeur d’Alene’s, four warriors and their families, and all the goods taken from Colonel Steptoe after he was defeated just outside of what is now Rosalia, Washington as his hostages, prisoners, and spoils. As they headed back into Spokane territory to do the same thing to the Spokane nation, they burned more food cashes and, according to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, some villages along their way. The Spokane’s signed a treaty on September 23rd, 1958. That original is conveniently missing too, leaving us with a copy of the preliminary treaty and list of participants. Col. Clarke’s endorsement calls out Col. Wright as being too lenient with article five, which stated “The foregoing conditions being fully complied with by the Spokane nation, the officer in command of the United States troops promises that no war shall be made upon the Spokane, and further, that the men delivered up, whether as prisoners or hostages, shall in no wise be injured, and shall, within the period of one year, be restored to their nation.” Clarke had demanded an unconditional surrender before Wright left Walla Walla. He noted, “It is now too late to repair the error; the prisoners are but hostages and as such will be kept as long as it may be proper to do so.”

The dehumanization was evident. The treaty, rather than being a bridge, was a box.

[i] Kip, Lawrence. Indian War in the Pacific Northwest: The Journal of Lieutenant Lawrence Kip. University of Nebraska Press. 1999. Print.

[ii] Bischoff, William N. and Gates, Charles M. Gates. Notes and Documents: The Jesuits and the Coeur d’Alene Treaty of 1858. Seattle. University of Washington. 1943. Print. https://digitalcollections.lib.washington.edu/digital/collection/lctext/id/6645

[iii] Heppner, Francis J.. Reference Service Report: Treaty Made in 1858 Between the United States and the Coeur d’Alene Indians. Washington D.C.. 1962. Print. https://ourcommunityhistory.net/s/ourcommunityhistory/media/1855